The Thingamajig and the What’s-It… and the Genius of Al-Abnoudi

They never learn,

nor did what came before teach them;

they hear nothing in this world but their own words,

and they have no place in the dialogue of soil and clay.

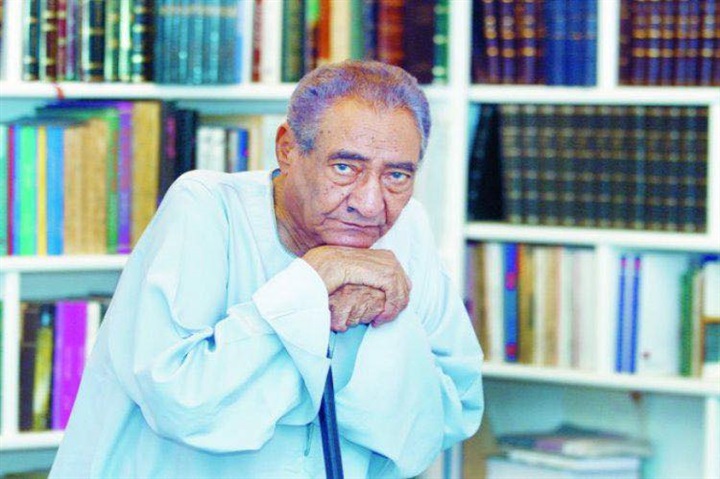

Did Uncle Abdel Rahman Al-Abnoudi know that the “thingamajigs and what’s-its” he pointed to so plainly—when he gifted me his final collection, Al-Abnoudi’s Quatrains, in April 2014—would be succeeded by their lookalikes: slipping into important institutions and venerable syndicates under the guise of democracy and freedom of opinion and expression, only to hijack them soon after and erect their own dictatorships and diseased ideologies within?

And did Al-Abnoudi imagine that, after a great revolution on June 30, 2013 that overthrew their predecessors and made them taste bitter humiliation, we would be startled by the return of the same foolish faces—peering out at us with their stupid mugs, threatening and blustering like hollow drums, in the manner of those before them when they brandished the Rabaa and Nahda sit-ins in the faces of Egyptians?!

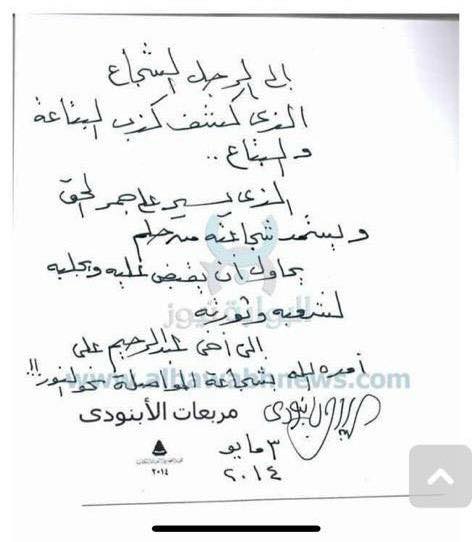

In the dedication—which I still keep in my library—the Uncle wrote:

“To the brave man who exposed the lies of the thingamajigs and what’s-its, who draws his courage from a dream he strives to grasp and bring to his people and their revolution; to my brother Abdel Rahim Ali—may God grant him the courage to persevere toward the light.”

Yes—toward the light, not the darkness they want us to cross into on bridges they built of hatred, obstinacy, and stupidity, seeking revenge against those who made their comrades and allies—from the Muslim Brotherhood, the April 6 Movement, and the supporters of Alaa Abdel Fattah and his companions who launched the slogan “Down with military rule”—taste bitter humiliation. That slogan still adorns their wretched pages, without shame or any sense of the need to apologize to the families of those who sacrificed their lives for this country—whom they called “the military.”

In the last calls between me and the Uncle, he charged me with Egypt, saying:

“Don’t leave the traitors—hunt them down to their graves.”

What bound us was the feeling of the stranger and of estrangement. We lived in Cairo, yet never truly belonged to it. Our roots pulled us back to where we were born and raised, where we played and made friends—to the formative years in the forgotten palm towns of Upper Egypt.

When we—he and I, along with the great screenwriter Wahid Hamed—were preparing the series Al-Gama‘a, we met at the Grand Hyatt. The Uncle surprised me by saying, “Have you written the land over to the girls yet, or not?” It hadn’t crossed my mind what was on his mind; I thought he was teasing me as usual. Then I was startled to see seriousness etched on his face. “I’m talking to you seriously. These people won’t leave you alone. Go write everything you have over to your daughters. Don’t you have three?” I said, “And I also have Khaled, Uncle.” The great poet smiled and said, “You managed to get yourself a boy—good.”

Three months ago my daughter Shahanda said to me, “I want to talk to Professor Abdel Rahman.” I said, incredulous, “Who’s Abdel Rahman?!” I had never called him by his name; I always called him “the Uncle,” like all his friends, disciples, and lovers. She said, “I mean the Uncle.” When I called him and handed her the phone, she came back to me overjoyed. The Uncle told her what he used to tell me to encourage me to carry on. Shahanda has kept telling her friends what the Uncle said about me to this day; she knows well the Uncle’s standing in Egyptian and Arab society as one of the foremost sages of our time.

We learned from the Uncle how to love our country through Ibrahim Abu al-‘Uyun. When friends asked me—after the Brotherhood came to power—“Why don’t you emigrate?” I answered the same way Uncle Ibrahim Abu al-‘Uyun answered the Uncle when he asked him after the June defeat: “Why didn’t you leave that land like everyone else, Uncle Ibrahim?” The man’s answer, which Al-Abnoudi set down in his brilliant collection Faces on the Shore, always lived within me: “People run off with their lives, my boy, but my life is right here before you in this land—where would I take it and go?”

My belief—still—is what Uncle Abdel Rahman Al-Abnoudi taught me: the homeland is a creed; and a homeland we do not confront them for is betrayal. Our sinews hardened by reading his poetry, and gray invaded our heads from memorizing his lines. The Uncle was not merely our beloved poet; he was a father and a friend, the chronicler of our lives and days. Through him we learned how the communists’ aloofness from the people caused them to lose sympathy for themselves and their ideas—“If you’re not going down to the people, then don’t bother.” We came to grasp the depth of the June defeat through his famous song voiced by the Nightingale Abdel Halim Hafez:

“Day passed, and dusk is coming,

hiding behind the trees’ shade;

and so we lose our way on theroad,

it took the moon from our nights.”

We learned a philosophy of death from his magnificent poem “Yamna”:

“When death comes to you, my boy, strip bare and meet it—you’re the winner.

Don’t count it up… no boy, no girl;

this is a time when a liar might tell the truth.”

When death came, Al-Abnoudi carried out Aunt Yamna’s injunction to the letter. He didn’t try—as she told him—not to add a day to his days, for whoever tries to add a day to his days is a donkey. Al-Abnoudi was human—but not like the human of this age. He was never a traitor, nor a Brother—even among their allies or the lemon-squeezers. He hated the very mention of the Brotherhood as he hated the mention of the Zionists. He loved poetry, the poor, Egypt, and his daughters, Aya and Nour.

Was it death that defeated Al-Abnoudi, or was it his unceasing struggle throughout the years following January 25, 2011 that exhausted his heart and delivered it to death? Al-Abnoudi rejoiced in the revolution and sang for it—then the thieves came and stole it from him and from us. Al-Abnoudi grieved and began his battle anew. “Rest isn’t written for us, my boy,” he told me. “You and I were created for battles and sorrow, nothing else. As for joy, Uncle—it has its people.”

I remain true to the covenant, Uncle.

I will not stop fighting them for a moment, until this country is cleansed of their filth—along with their allies bearing the April 6 slogans, the Revolutionary Socialists, and the enemies of Egypt’s great army and its men,

those who raised in the faces of its martyrs and their children the slogan, “Down with military rule.”

“I will hunt them, Uncle, to their graves. I will fear none of them.”

And it is a promise upon me that I will bring you the news of their imprisonment—soon—just as we imprisoned their predecessors after a pledge we made to them openly in Tahrir Square on May 17, 2013, when they were at the height of their power.

So sleep with eyes at ease… and enjoy peace.

Paris: 5:00 p.m., Cairo time.