The Womb of Memories

When I turned my face toward the city of Paris—dwelling in it as it dwelt within me—I was searching for my lost object in love, revolution, and life; that sacred trinity that had pursued me for a third of a century, or more.

I turned my face toward it, trying, in what remained of life, to discern what I had failed to notice in my youth, when I used to visit it alone on winter nights, walking through its streets… seized by the eyes of passersby, the shops of the Champs-Élysées, the cafés of Saint-Michel, and the musicians in the metro stations… I stared into all the bottles of life—they were empty… and I stretched my gaze into the distance, seeing no one but you… neither faces nor mirrors, neither wine nor churches—nothing but you inhabited me, in presence and in absence.

This time I leave you behind as a beautiful dream that has lived within me since I was a child; some may differ in interpreting it, but it was the cry of a man born from the womb of memories, who placed his dream upon the altar of passion, a necklace of love offered to you… I leave my homeland by choice, loving, enamored, searching for my lost object, tracing your footsteps upon the foreheads of lovers…

On the banks of the Seine, I remember my distant town in Upper Egypt and weep, but I hear my father’s voice chasing me with his favorite phrase: “Men do not cry”… that was a long time ago.

Was I old enough then for my father to burden me with his sole injunction? Or was it his myth that has pursued me until now?!

In the Place de la Concorde, where the ancient Pharaonic obelisk stands, the famous Hôtel Le Crillon, and the eastern wing of the Élysée Palace… I remember that pale, elegant woman… who once told me that my grandfather had taught her a lesson with a stick across her back when he caught her singing, “Take me to my beloved’s land…” She threw herself into my arms and wept… I resembled her greatly, and I liked to remind her of that moment again and again, and then we would laugh… She is far away now, absent in stillness, yet she lives in my heart wherever she has gone, just as I once inhabited her soul and her womb sixty-three years ago.

I was not among those born with a silver spoon in their mouths; we were called the sons of the poor. We carried the burdens of our generation, the burdens of the marginalized, and above all the burdens of the homeland. We bore them in our hearts and minds, dreaming of a better tomorrow, until the bones grew frail and the head ignited with gray.

I was one of many whom the wave of the left drew early on (in 1977) toward the sea of knowledge, literature, and culture. From our earliest years, we came to know modern Egyptian history through al-Jabarti, Abdel Rahman al-Rafei, Tarek al-Bishri, Abdel Azim Ramadan, Uncle Salah Issa, and our elder who taught us magic… Refaat El-Saeed.

We memorized and internalized, by heart, the poetry of Fouad Haddad, Salah Jahin, Ahmed Abdel Muti Hijazi, Amal Dunqul, Mahmoud Darwish, Adonis, Youssef Al-Saigh, Abdel Rahman Al-Abnoudi, Ahmed Fouad Negm, and Muzaffar al-Nawwab. We read the stories of Yahya Taher Abdullah, Abdel Rahman Munif, Hanna Mina, Rachid Boudjedra, Haidar Haidar, Tayeb Salih, and Tahar Wattar.

Before all of them stood our deep familiarity with the dean of the Arabic novel, Naguib Mahfouz, and the genius Youssef Idris. Early on, we blended history with literature, poetry with storytelling, song with music, cinema with theater. We bought books collectively and read them individually. Early on, we confronted religious violence groups in their stronghold in Upper Egypt, in Minya; and we sang with Mohamed Mounir, “If we stop dreaming, we die.”

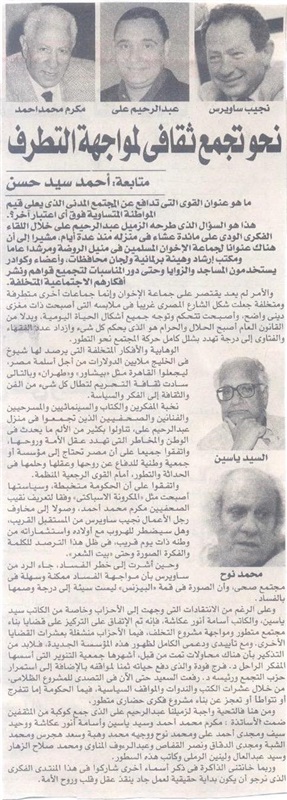

We lived with Osama Anwar Okasha the epic of Layali al-Helmiya and Arabesque, and we never raised the white flag… When he visited me at my home in 2008, having written an article about me in Al-Wafd newspaper, my wife and daughters thanked him. He and I, along with the elders—El-Sayed Yassin, Mohamed Nouh, Naguib Sawiris, Makram Mohamed Ahmed, Wahid Hamed, Lenin El-Ramly, Wagih Wahba, and Magdy Ahmed Ali—shared a simple dish of ful beans with seasoning prepared by “Umm Khaled.” Khaled was still young when he saw the elders in our home and took photos with them to show his classmates. Years later, when Mofeed Fawzy came to my house to interview me for his famous program Keys, Khaled proudly showed him those photos, saying, “You are not the first celebrity to enter our house.” Professor Mofeed laughed when he understood Khaled’s intent.

I now recall those meetings… It was the summer of 2008, and we were in the process of founding an institution called the Egyptian Liberal Forum, whose mission was to confront the Muslim Brotherhood—not only intellectually and in the media, but also on the ground, socially, through associations that would provide the same services the group offered. But Major General Habib El-Adly, the interior minister at the time—may God forgive him—had a different view, and the project was aborted… Recently, I was a guest at Mrs. Nelly Gabor’s salon to discuss regional conditions, where I met engineer Salah Diab. To my surprise, he recalled memories of that meeting and accused me of being the reason he was summoned at the time to be questioned about his relationship with me, with the meeting, and with the idea—though the man had no connection to the matter then other than Al-Masry Al-Youm having published about him.

That day, Wagih Wahba said that had the government allowed us to implement the idea, the face of the country would have changed, and the Brotherhood would not have reached the level of entrenchment in Egyptian society they achieved in the years leading up to January 2011.

I had prepared that idea and presented it to engineer Naguib Sawiris, discussing it with the professors El-Sayed Yassin, Makram Mohamed Ahmed, Wagih Wahba, Lenin El-Ramly, Osama Anwar Okasha, Mohamed Nouh, Magdy Ahmed Ali, Wahid Hamed, Ahmed Sayed Hassan, and Magdy El-Dakkak… We held three meetings for it: the first was a working dinner at my home, and the other two were held at the Garden City Club owned by Sawiris. In the second meeting, I presented the general program project; we chose El-Sayed Yassin as president, and those present chose me as secretary-general. But the project was swiftly strangled in its cradle after the third meeting, by instructions from Habib El-Adly at the time.

I do not know why memories pile up in my mind as I review my new days… Is it because sorrow stands against time? Against whom? And when did the heart, in its pounding, find reassurance?!

In those years—the formative early years—we watched with Galal Abdel Qawi the “choices” of the brothers in Al-Mal wal-Banoun, and we learned from Ali El-Haggar that the devil “cannot overpower one whose goodness is for others.” So we loved belonging to the poor and the marginalized, and we sang for them and with them songs of love, revolution, and life… We predicted the coming danger with them and tried to avert the catastrophe, but no one listened, even though President Mubarak himself asked the late Sheikh Mohamed Sayed Tantawi and the Mufti Ali Gomaa—then still alive—to sit with me and review what I had written about those groups, especially the Brotherhood, describing me as “Egypt’s artilleryman” against terrorism, its groups, and their allies… I sat with them, and my relationship with both men deepened. Perhaps I will find time to write about that period, when some politicians and intellectuals—still well known today—were heralding the Brotherhood’s project, without awareness or knowledge.

I was, and remain, deeply indebted to the school of the left—especially those who respected the traditions, customs, and culture of Egyptians and Arabs; who respected that we are the children of that Arab civilization which brought together Muslims and Christians of the East and fused them into a single crucible. Those who found no contradiction in praying the dawn prayer with Surat Ya-Sin, or going to church on Sundays and reading passages from the Gospel, then returning home to open Capital and read a chapter, forming a new consciousness for a civilization open to the other. They did not entrench themselves behind the Third International fabricated by Stalin to entrench his dictatorship; rather, they opened themselves to Leon Trotsky, to European socialism, and even more to liberal thought, taking from each experience what it offered. They understood the role of literature and art in the struggle of peoples, and engaged in every experience that exalted the value of the human being—any human being—defending the value of freedom of thought and creativity. They drank deeply from the greatness of Kazantzakis, Kafka, Pablo Neruda, and the genius Victor Hugo.

They respected the value of individuality and innovation, and thus were truly pioneers of a different generation—a generation I almost say, without sophistry or arrogance, made itself by itself. It had no teachers in the traditional sense of the word, but was open to all experiences, emerging solid and strong, aware of the value of itself and its homeland. Thus it was able to stand firm, without clamor, against the Tatars of the new age, and to survive what everyone else fell into—those who made of themselves a bridge over which the Tatars crossed, those who squeezed lemons and stood in the famous Fairmont Hotel, paving the way for the coming of the Mongols.

Venice: five o’clock in the afternoon, Cairo time.