There was what there was… the ear of wheat deceived us

You are enchanting,

and I am aged;

you are enchanting,

seeking love, yet I

am tracking a lost trace.

We should have met in my youth;

then I would have loved you with a madness of love,

but instead we went on together.

Those famous lines by our great poet Ahmed Abdel-Moneim Hegazy distilled the tragedy of the intellectual who lived chasing a lost trace, and thus missed the train of love and life.

So it was with us when we set out for Cairo of al-Muʿizz nearly forty years ago or more, at the beginning of the eighties of the last century.

Our innocence was hidden in the arithmetic book, and the dream ran ahead of us, hair and soul disheveled, panting with bewilderment. We followed its breathless run, crying and laughing, mingled with the warmth of memories and the shimmer of hopes.

Such were the features of our spirit as we pursued our dream through the streets of the Mahrousa, our bodies brushing against its cafés. We sipped knowledge and debated the courses of history, inhaling the scent of the novel and the aroma of poetry in Riche and Zahrat al-Bustan, where were faces that bore the burdens of the nation—faces from classes weighed down by the burden of truth alone, beyond what their arms carried of venerable, heavy loads.

A world of paper, remnants of women, and a train passing, trampling the façades of cities… that was our legend.

In those cafés we came to know faces poised between absence and presence: the brilliant critic Ibrahim Fathi; the translator and Trotskyist historian Bashir al-Sibai; the exceptional novelists Ibrahim Aslan, Gamal al-Ghitani, Ibrahim Abdel-Meguid, and al-Makhzangi; and the poets of the Seventies generation: Helmi Salem, Refaat Salam, Hassan Talab, and Abdel-Moneim Ramadan.

We were colleagues to some, friends with others; politics parted us from a few, yet we never lost the compass of affection among us.

We belonged to the school of the Left. I remember how we came from our distant villages, advancing on Cairo of al-Muʿizz, laden with the dreams of the poor for justice and freedom. We headed straight for Refaat al-Saeed’s office, the pilgrimage site of leftists then, and as was our habit we needled him about the party’s retreat and its softness toward the nation’s causes.

Al-Saeed laughed and said:

“A time will come when we are preoccupied away from it, and you will weep… two weights are different, and a heart divided by two schedules of love and blows.”

At the time, Al-Ahali newspaper was distributed at one hundred and fifty thousand copies, and the Tagammuʿ Party was issuing a booklet headlined in bold type:

“We will not elect Mubarak for a second term.”

We saw all of that as “nonsense,” because it did not come within a call for chaos—I mean revolution—as we wished and believed then.

We were young at the time; we said of him what Malik said of wine, yet we loved its spirit. We were not criticizing him; we were criticizing the conditions that prevented us from realizing our dreams in a homeland to which we belonged and which belonged to us.

We did not come from the middle class; we were, and remain, called the sons of the poor. We never disavowed our past, nor our families, nor our teachers.

Al-Saeed departed one day in 2017, after sharing with me the founding of the dream “Al-Bawaba,” of whose board he was a member, alongside other departed greats: Sayyid Yassin, Mohamed Hafez Diab, and Qadri Hefni—from whom I learned that keeping company with the great means rising above the practices of the small.

It is time for me to confess—just as all my fellow leftist rebels confessed to me before—that we loved Refaat al-Saeed as much as we criticized him, perhaps because we could not outpace his steps.

The elderly sheikh always preceded us in vision, analysis, and responsiveness to reality. When we withdrew to chase our dreams, he stayed with reality, studying and analyzing it, and emerged from it with the correct vision and stance.

Even when I submitted my resignation from the Central Committee in April 2010, in protest at the party’s reception—within a framework of coordination—of members of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Guidance Bureau, led by Mohamed Morsi al-Ayyat, then responsible for the group’s political file, he did not grow angry with me. This was despite the fact that most newspapers and websites published the resignation at the time, publicizing the party and commending my position; he nevertheless showed understanding.

I reveal no secret when I say that he told me: had I been in your place, a member of the Central Committee, I would have taken the same position; but my burden is heavy—I am the party chairman, and my resignation would mean its explosion, or at the very least leaving it to those allied with the Brotherhood.

That day he contented himself with boycotting the meeting he had called, which was to include the late Abu al-Izz al-Hariri and Anis al-Bayyaʿ.

Years passed, and I was no longer the youth I had been at nineteen…

From Madbouli to Al-Shorouk, passing through our late friend Mohamed Hashem at Merit and Dar al-Maʿrifa, and Dar al-Hilal Bookshop, and later the Azbakeya Wall—our knowledge took shape, and we carved our first steps toward literature and history.

We came to know al-Jabarti, Ibn Iyas, al-Rafiʿi, Salah Issa, Abdel-Azim Ramadan, and Tariq al-Bishri.

With them we learned other paths of history that we had not been taught in our old schools, and we realized then that there were many theories and positions that compelled us to reconsider all the phenomena and events the nation had passed through. Fortunately, we grasped this in our youth, before it was too late.

We learned early at the hands of a generation that knew no compromise when it came to truth: Ismail Sabri Abdallah, Fuad Morsi, Ibrahim Saad al-Din, and Milad Hanna.

Before them, we had already drunk deeply from Taha Hussein, Ali Abdel-Razek, and Louis Awad—that strung necklace of pearls that still adorns the chest of the Mahrousa.

Between the streets of Downtown and its passages, our boats sailed to dock us at a new phenomenon that befell the nation and caused it pain.

The emergence of Islamic groups, with their various sects and organizations, was a turning point that shifted our compass from studying the Left to studying Islamic thought and the products of those groups.

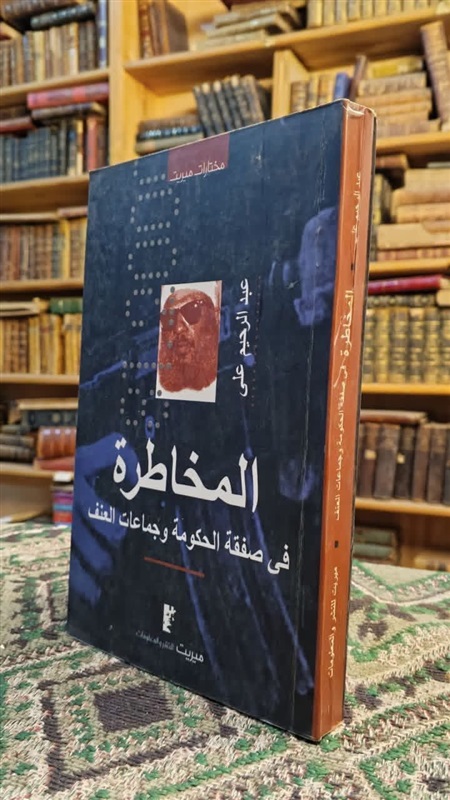

I had then just passed my early thirties and began writing my first long study, later published as a book by Merit Publishing House under the title:

“Risk… in the Government’s Deal with Violent Groups,”

with a cover designed by the creative Ahmed al-Labban.

That study was the product of five years of reading the ideas of those groups and comparing them with Islamic thought in its period of flourishing with Ibn Rushd and his school, and those who followed their path in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—a long chain of luminous names beginning with Sheikh Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi and not ending with Mahmoud Shaltout, passing through Sheikh Hassan al-Attar, Imam Muhammad Abduh, Sheikh Mustafa Abd al-Razek, Ali Abdel-Razek, Amin al-Khuli, Abdel-Mutaʿal al-Saʿidi, and Mahmoud Abu Rayya.

In that study I documented the state’s method of dealing with those groups, which was based on striking bargains with them, and I warned that this method might ultimately deliver them to the Ettehadiya Palace. What befell me and my feverish publisher friend Mohamed Hashem at the time befell us because of publishing that study, whose repercussions continued to cascade through Arab and international newspapers and magazines for years, until the events of September 11, 2001, took us by surprise.

I recall that I wrote in the dedication then:

To Khaled Abdel-Rahim…

Fifteen years from now, you will see and witness strange phenomena and even stranger manifestations, which your father had seen and witnessed before, when locusts advanced upon your grandfather’s beautiful town in Upper Egypt. At that time, I hope you will know that your father did not stand silent.

And there was what there was in January 2011…

The ear of wheat deceived us,

then the swallow cast us to the winds of the killers.

Paris: five o’clock in the evening, Cairo time