opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum… “Al-Bawaba News” republishes the story of the boy who discovered the steps to the tomb of the Golden Pharaoh

Saturday 25/October/2025 - 08:32 PM

Shahenda Abdel Rahim

“Nubi,” son of Hussein Abdel Rasoul, tells Al-Bawaba News: “My father was the true discoverer of Tutankhamun’s tomb.”

As Egypt prepares to celebrate the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum — an event the entire world awaits to witness Egypt’s glorious civilization — all are ready for a journey through 5,000 years of history in a single day and in one place: the Grand Egyptian Museum, Egypt’s gift to the world.

On this occasion, Al-Bawaba News republishes its exclusive interview with the only surviving son of Haj Hussein Abdel Rasoul, the man who discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb — Mr. Nubi Hussein Abdel Rasoul.

The Abdel Rasoul Family — Guardians of Luxor’s Ancient Secrets

It is impossible to visit Luxor, in the heart of Upper Egypt, without hearing about the Abdel Rasoul family. You might hear their story from a tour guide explaining the early archaeological discoveries of Luxor, or while sitting in one of the cafés or restaurants of the city. The Abdel Rasoul family is among the most famous in Luxor; they own cafés, hotels, and other establishments in the West Bank, particularly in Qurna — the area that hosts most of the foreign archaeological missions working to excavate Egypt’s treasures.

The family became renowned for major discoveries, including the cache of forty mummies unearthed by their great-grandfather in what became known as the Deir el-Bahari Cache. But the most famous tale associated with their name is that of the 12-year-old boy, Hussein Abdel Rasoul, who found the first step leading to glory — the step that guided Howard Carter to the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun.

Unraveling the Truth Behind the Discovery

Many mysteries and conflicting accounts surround this story. To uncover the facts, we traveled to Luxor to meet the only surviving son of Hussein Abdel Rasoul — Nubi Hussein Abdel Rasoul.

■ Your father, Haj Hussein Abdel Rasoul, was only 12 years old when he played a role in discovering Tutankhamun’s tomb. What exactly was his role?

— My father, Hussein Abdel Rasoul, was a young boy working with my grandfather, Mohamed Abdel Rasoul. My grandfather was the one who discovered Hatshepsut’s Deir el-Bahari cache of 40 mummies in 1885 — which were later transferred to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in the royal mummies parade.

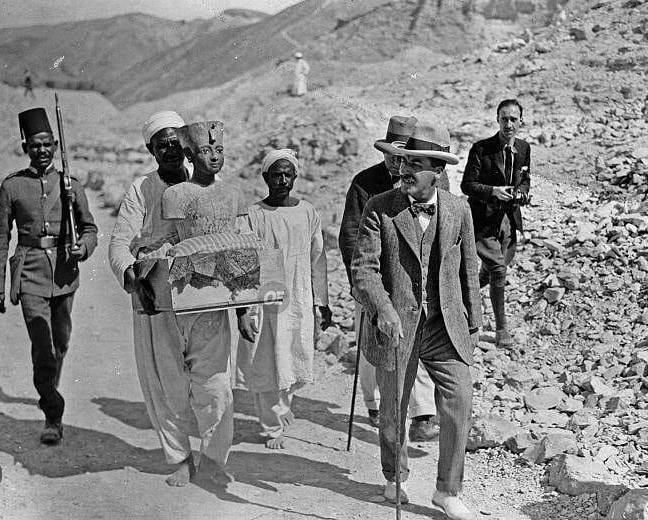

At that time, Lord Carnarvon was funding Howard Carter’s excavations. The two met by chance while Carter was working as an artist near the Winter Palace Hotel and Luxor Temple, sketching scenes for tourists to earn a living. Carnarvon told him about a royal tomb in the West Bank, and knowing that the Abdel Rasoul family were experts in antiquities, he advised Carter to seek their help.

Indeed, Lord Carnarvon and Carter came to the area and met my ancestors. Step by step, they began their search — until they discovered the tomb. My father was behind this discovery. He was only 12 years old then and was nicknamed “the water boy” because he helped workers fetch water for free. He used to ride a small donkey, carrying water jars. One day, as he was unloading the water, a few drops spilled and fell onto an uneven surface — the first step of the tomb.

At that moment, Carter’s excavation mission was nearly over, and he was losing hope. Work had begun in 1912, then stopped during World War I (1914–1918), resuming afterward. The actual discoveries began in 1920, and the tomb was uncovered in 1922.

When my father discovered the steps, Carter rejoiced. My father told him, “There’s something like a stair here.” When Carter saw the steps, he ordered the digging to begin. Normally, he never greeted the workers, but that day, out of joy, he embraced them all and called it the “Day of Days.”

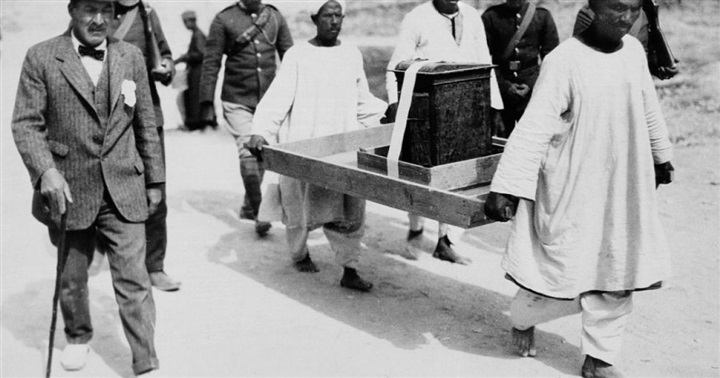

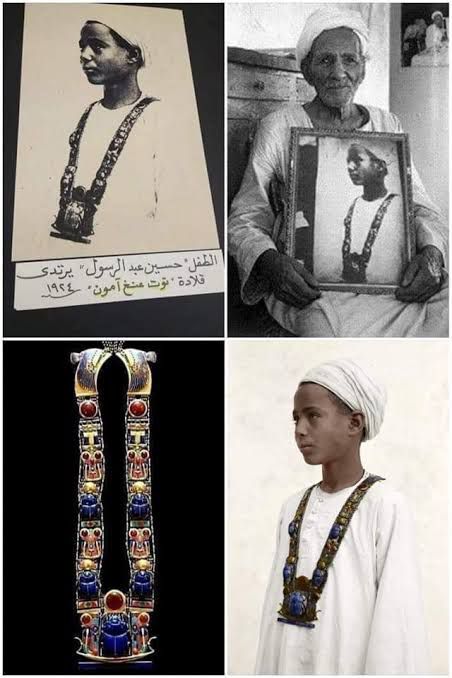

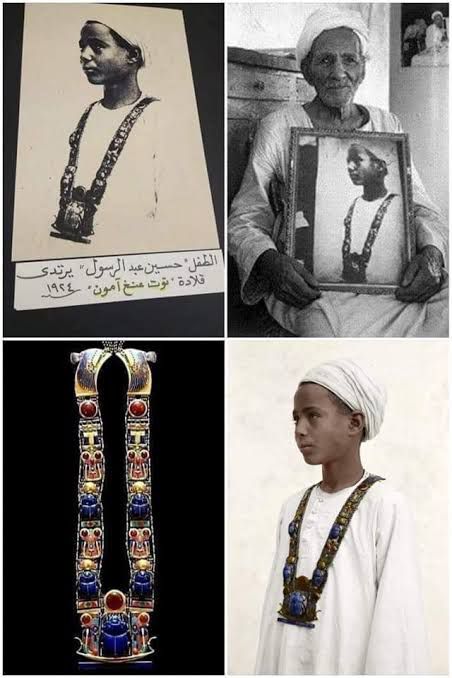

The workers continued for months, extracting the treasures and golden artifacts. Carter found the famous necklace and, believing it brought him good fortune, placed it on my father and took a photograph of him wearing it. A week later, the government reclaimed the necklace, which now rests in the Egyptian Museum.

■ There are many rumors about the Abdel Rasoul family — from discoveries to thefts. What is the truth?

— Our family has a long and honorable history in archaeology. My grandfather funded some excavations at his own expense out of love for his country. He was one of the leading landowners in the area. We had nothing to do with thefts — antiquities smugglers are known by their lavish wealth, and as you see, that was never our case.

When rumors about thefts spread, the authorities intervened — even though, at the time, the real thefts were committed by powerful pashas. Yet the stigma stuck to our family unjustly. We never stole a single artifact — the forty mummies discovered by my grandfather are all in the Egyptian Museum today.

■ Do you or your family take part in documentaries about the Valley of the Kings and these discoveries?

— Nowadays, archaeological missions are run by the Ministry of Antiquities. In the 1960s, there were no professional inspectors, so they relied on members of our family. Every mission that came here would meet with my father and uncle. Today, we still record interviews with foreign TV channels — there isn’t a single major international network that hasn’t filmed with our family, in addition to Egyptian channels.

■ Your family also owns the famous Atelier Hotel, which is over a century old. What is its story?

— The hotel dates back more than a hundred years. It gained fame among European missions that came to excavate in the Valley of the Kings and the West Bank. At that time, only three hotels existed in Luxor: our family’s hotel, the Winter Palace, and the Savoy on the East Bank.

Foreign visitors preferred to stay on the West Bank to be near the excavation sites. Europeans always sought a change from their lifestyle and atmosphere, desiring something rural and authentic. Back then, five-star hotels didn’t exist, so they were fascinated by the rustic charm of our hotel — and they were the ones who promoted it abroad.

■ What fields do family members work in today?

— The younger generation grew up hearing about our ancestor, the famous boy Hussein Abdel Rasoul, and our family’s role in discovering Egypt’s treasures. Naturally, they developed a passion for archaeology — some became tour guides, others antiquities inspectors or restoration specialists. Unfortunately, we haven’t been given our due in official archaeological appointments, though some relatives now work as guides or inspectors. My own son is a first-year student in the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels.

■ Tell us about tourism in Luxor. Has it been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war?

— Tourism in Luxor is currently good, though it was, of course, affected by the pandemic and has been recovering gradually. The Russia-Ukraine war also had an impact, mainly on beach tourism in Sharm El-Sheikh and Hurghada, as most visitors there are from Russia, Ukraine, and neighboring countries.

In Luxor, however, tourism is cultural — most visitors come from Germany, Britain, Spain, Italy, and France. Some of them even own homes here and are married to Egyptians.

■ What does the renowned Egyptologist Dr. Zahi Hawass mean to you?

— Dr. Zahi Hawass is one of the greatest Egyptologists — a scholar and a reference for archaeologists and excavation missions. He is also a true ambassador for Egyptian tourism.

■ What is the story of the American director who was amazed by your son’s resemblance to Hussein Abdel Rasoul?

— An American director came to film a movie about the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. He was looking for a boy to play the role of Hussein Abdel Rasoul at age 12. I sent him a photo of my son wearing a white shawl. He replied that he wanted a real actor, not a photo. When I told him it was indeed my son, he couldn’t believe the striking resemblance to my grandfather.

■ Howard Carter’s house in Luxor is now a famous tourist site. Do you believe your family deserves that recognition instead?

— Carter was lucky. After Lord Carnarvon funded his excavations, the Egyptian government appointed him as an archaeologist and built him a residence here, which became famous. Meanwhile, our family — who helped him make the discovery — never gained such recognition.

■ How did people live so close to the mountain and the Valley of the Kings?

— All the houses here were built of mudbrick, because concrete construction was prohibited near the mountains. The whole area near the Valley of the Kings used to be inhabited. In 2010, residents were relocated to a new area called New Qurna City.

In the past, archaeologists used to stay in local houses near the mountains — the German mission still has one here, and the Polish mission has another near the Temple of Hatshepsut. Near the Valley of the Queens, there’s also an area called El-Malqata, meaning “the place of tombs.”